At 6 am, back in Seattle, I would definitely still be sleeping. My earliest school mornings entailed bundling up for my biology labs and trekking across campus in the rain. I never expected that for the fall quarter of my third year at the University of Washington, I would wake up at 4:30 am for a morning sea turtle census. Now, I walk to the outdoor bathroom and showers, my headlamp the only apparent light source, with howler monkeys roaring in the jungle nearby. And by 6 am, I am releasing baby sea turtle hatchlings into the Pacific Ocean’s warm waters from the Osa Peninsula coast in Costa Rica.

My Sea Turtle Conservation Internship allows me to complete a quarter of fieldwork study at Osa Conservation— a nonprofit organization dedicated to protecting and preserving the biodiversity of the Osa Peninsula, allowing me to observe wild and beautiful forms of nature in the tropics. Early morning wake-ups prepare us to go out on the morning census, where we monitor Piro Beach, a 2 km long nesting beach for the threatened olive ridley and green sea turtles. The Tortuga (turtle) Team is a small collection of interns from around the world, united by our love for nature and wildlife. We find and relocate threatened nests to the hatchery, record essential data to assess population trends and predation rates, and complete post-hatched nest excavations to determine hatching success. As interesting as data collection is, the most enjoyable and rewarding part is releasing the baby sea turtle hatchlings.

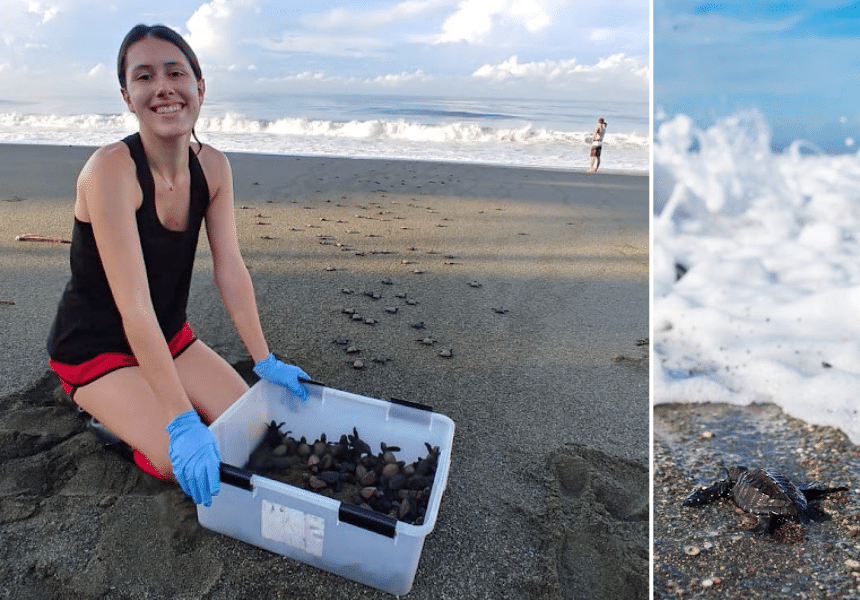

The hatchery is an open mesh structure that encloses part of the beach, with bamboo posts as support beams. This is where we relocate and rebury threatened nests, and around 60 days later, they hatch. We walk along the beach to reach the hatchery and check our baskets for any hatched nests. We use baskets so the hatchlings do not wander loose, and to keep the data for each nest and treatment group organized.

These baskets house masses of tiny wriggling figures climbing over each other to reach their innate destination: the ocean. They’re greenish-brown, sandy, and small, and their tiny flippers pedal against my fingers as they wriggle for freedom.

From the baskets, we move them to buckets and walk outside the hatchery to the beach. On the beach, I feel the damp sand and hear the crash of large waves as the mist from the ocean casts a slight fog over the rainforest. Insects chirp all around us and the occasional bird calls in the distance. We lift them from the buckets, and once placed onto the sand, they immediately crawl towards the water, carving small trails into the otherwise pristine surface. My eyes grow sore from gazing across the bright beach to trace their paths, but I feel comfort in knowing I played a part in protecting such brilliant creatures.

I would never have expected to be such an early riser, let alone enjoy it. Coming to the jungle for three months was one of the boldest decisions I’ve ever made, and I’m happy I stepped outside the environment of Seattle I’m used to.

National Geographic describes the Osa Peninsula as “the most biologically intense place on earth,” and I agree. I am humbled and in awe of the wildness here, and I wouldn’t have wanted to spend fall quarter any other way. I awake each day grateful for what I’ve learned, the people I’ve met, and the places I’ve seen. Now, I’m motivated to wake up earlier than ever and go save some baby sea turtles.

Kylie Baker is an aspiring outdoor communicator and won first place in the 2023 OWAA Norm Strung Student Writing Contest.