It could be fair to say the eight people who put their names on the statement creating the Outdoor Writers Association of America had little idea what the fledgling organization would become or that it would last as long as it has.

Their collective interest was elevating the status of outdoor writers, which they felt was being undercut by less reputable storytellers.

Jimmy Stuber, who served as OWAA’s secretary from 1929 to 1944, summarized the situation in an article for the Pittsburgh Press:

“Outdoor writers who had won their spurs through experience were griped at the counterfeit, the phony and the bunkum which crept into so-called outdoors columns and magazine articles as well. The reading public was being duped by ‘pikers,’ ‘quack writers’ and ‘clip artists’ who had never been there.”

The solution came in 1927 at the fifth annual Izaak Walton League convention in Chicago with handwritten words on the back of a banquet menu accompanied by eight signatures. With that, OWAA was born.

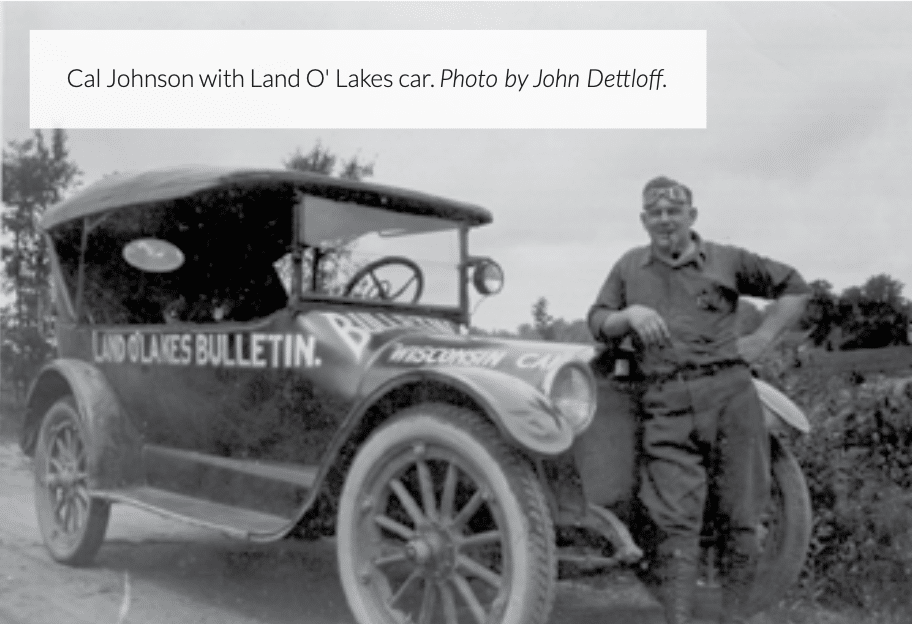

Morris Ackerman penned the OWAA Bill of Organization during the convention’s closing banquet. Later, a group of writers gathered again, according to one account, in Jack Miner’s room at the Hotel Sherman to elect officers.

OWAA’s organizers wanted only accredited writers. Once vetted and approved for membership, Stuber said they could “join those who knew the scent of pine and hemlock, the odor of a campfire being wafted to them in the wilderness or the deep stillness of a hidden lake.”

Ackerman was elected OWAA’s first president and was reelected in 1928 and 1929. Most of the other seven founders had leadership roles over the next few years. Buell A. Patterson was OWAA’s first secretary, and Edward G. Taylor was chosen honorary president in 1927 and 1928. Miner and W.S. Phillips (aka El Comancho) later served on the board of directors.

Records from the early years are incomplete, but recently uncovered evidence indicates Cal Johnson was elected president four times over the next decade. Peter P. Carney and Mrs. Hal Kane Clements, whose first name was Hazel, were the only co-founders who didn’t serve OWAA in some capacity.

At the time, Taylor was the oldest (71) and Patterson the youngest (32). The others ranged in age from 35 (Clements) to 61 (Miner).

Who were these people? Where were they from? What did they do to get a seat at the table on that April night in 1927 when OWAA was formed? Each of the eight had noteworthy and varied careers. Here are the stories for four of them.

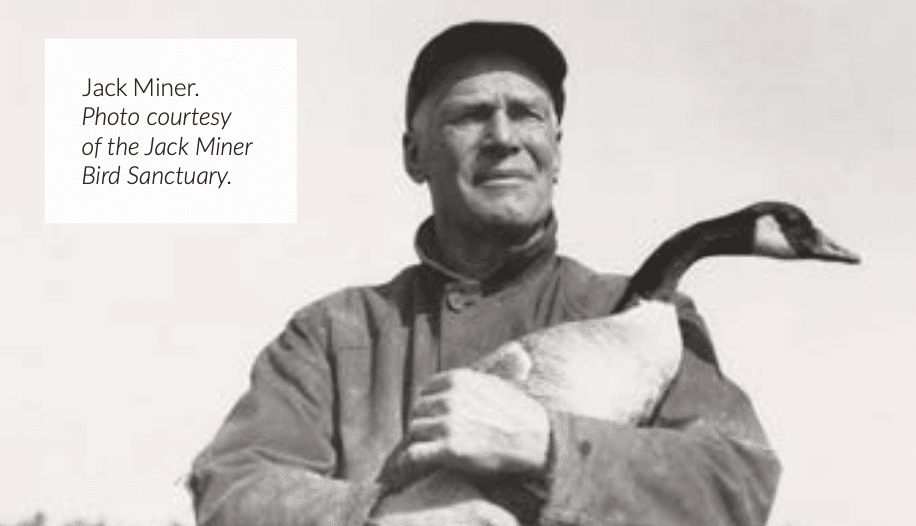

Photo above: Morris Ackerman fishing with Spanky McFarland. Photo retrieved from theCleveland Public Library.

Morris Ackerman (1883–1950)

Georgia-born Morris Ackerman earned a law degree from Western Reserve University in Cleveland—not so much to be a practicing attorney but to earn enough to support his true interests: fishing and hunting.

His degree took him to Grand Junction, Colorado, where he clerked in a law office and coached high school football. After his mother’s death, he returned to Cleveland to work in his father’s food brokerage.

While attending a food brokers convention in Baltimore, he noticed the local newspapers published tables of tidal, sun, and moon activity. Thinking such information might be helpful to anglers and hunters, he pitched his first outdoor story to the Cleveland Leader in 1912.

“I took a gamble,” said Ackerman, who was paid $5 for the article.

What followed was an illustrious career that included stints as outdoors editor for the Cleveland Press and Scripps-Howard Newspapers, syndication through the Newspaper Enterprise Association, and time as publisher of an annual fishing and hunting guide that grew to more than 300 pages before he turned it over to his son, Bill, in 1941.

He somehow found time to organize the American & Canadian Sport, Travel and Outdoor Show that began in 1927, took a break during the Great Depression, and after resuming in 1937, ran it for several decades before it closed.

Atlanta Journal outdoor writer O.B. Wells called Ackerman “one of the exceedingly few men I have met who earn an honest living doing exactly what they want to do.”

In a 1938 feature article in the Knoxville News-Sentinel, Joe Williams wrote:

“There is little about fishing that Mr. Ackerman does not know. He can tell you the domestic habits, political leanings, and social eccentricities of all the known denizens of the deep.”

At least twice, Ackerman had brushes with death—once as a boy when a gun discharged and grazed his forehead, and later while hunting grizzly bears in Alberta when a massive female rose behind him.

Ackerman fished or hunted with famous writers such as novelist Rex Beach, sportswriter Grantland Rice, and Hugh Fullerton, who broke the “Black Sox” scandal of the 1919 World Series. His outdoor companions also included baseball stars Ty Cobb, Walter Johnson, and Tris Speaker.

“I have fished and hunted with prize fight champs, baseball champs, football stars, bankers, brokers, actors, authors, millionaires, and poor men like myself,” he once said. “Any fishing or hunting shack is my home.”

Ackerman traveled widely in pursuit of fish, game, and stories—visiting all 48 states, plus Alaska, Canada, Europe, Mexico, and the West Indies. He spent three months each year in Quebec’s Gatineau Valley, where he leased 75 square miles of territory. By 1934, he’d made more than 50 trips to Canada and died of a heart attack in 1950 during his 23rd trip to Florida.

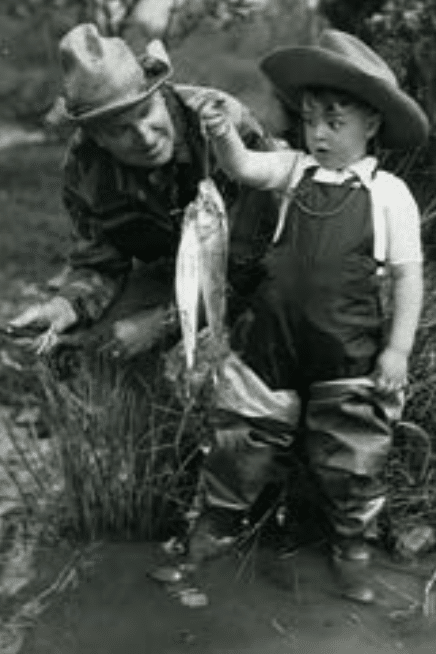

Cal Johnson (1892–1953)

Despite a career full of achievements as a magazine and newspaper outdoor writer and editor, radio and television broadcaster, and publicity director for outdoor manufacturers and the Izaak Walton League, Cal Johnson is best remembered for what he did after retirement.

On July 24, 1949, Johnson caught a massive muskellunge on Lac Courte Oreilles near Hayward, Wisconsin. It was weighed, measured, and certified as a world record—67 pounds, 8 ounces.

Three months later, Louie Spray claimed a bigger catch. Debate over the true record lasted decades, with different organizations recognizing each fish.

Johnson’s life before and after that day was equally remarkable. He wrote for Outdoor Life, edited Outdoor America, hosted Chicago radio shows, and contributed to Collier’s, Esquire, and Liberty. Diagnosed with a heart condition in 1947, he found healing through fishing and lived another six years.

“The outdoors is the greatest doctor in the world,” he said. “If you feel yourself slipping, go fishing—it is the world’s most soul-satisfying pastime.”

Jack Miner (1865–1944)

In a 1940s newspaper poll of North America’s most influential people, Jack Miner ranked fifth—behind Edison and Ford.

Born in Ohio and later moving to Ontario, Miner became one of the early 20th century’s most important conservationists. He founded the Jack Miner Bird Sanctuary and pioneered bird banding, helping track migratory patterns of ducks and geese.

He was also a charismatic public speaker and an early advocate of game protection. Honored with the Order of the British Empire in 1943, Miner’s work continues today through Canada’s annual National Wildlife Week, held in his honor.

Photo above: Edward G. Taylor. Photo retrieved from the Chicago History Museum.

Edward G. Taylor (1856–1945)

Taylor was a Chicago newspaper writer whose career began with the Chicago Inter Ocean and later the Chicago Daily News. Known for his column “With Rod and Line on Lake and Stream,” Taylor was one of the most prolific outdoor writers of his time.

He also wasn’t afraid to challenge authority—famously writing President Calvin Coolidge in 1927 to criticize him for using worms as trout bait, calling it “slaughter.”

Taylor’s influence was wide-ranging. His articles combined news, technique, and philosophy, and his contests and reader engagement helped build enthusiasm for fishing as both sport and lifestyle.

OWAA in the 1920s

After OWAA was formed and its first officers were elected, the group’s focus was on discrediting “nature-faking” writers and strengthening relationships with editors.

By 1928, members met again in Cleveland, voting to standardize the names of fish and game species. The “musky” was officially adopted as the preferred spelling for muskellunge.

At the 1929 convention in Chicago, OWAA saw growth and its first female member since Mrs. Hal Kane Clements. Proposals covered dues, insignia, and ethical standards for outdoor writers.

Not everyone applauded. A Detroit Free Press column in 1929 lumped OWAA with groups like the Rotary Club and the National Pickle Packers Association, accusing them all of shaping public thought—a humorous footnote in the history of an organization that continues to shape the voice of outdoor communication nearly a century later.

Phil Bloom is two-time president of OWAA and a lifelong resident of Fort Wayne, Indiana.