Photo above: Hazel Clements, Photo courtesy of the Clements family.

Editor’s note: In the history blog post, “Writers who changed outdoor journalism: The founding of OWAA”, Phil Bloom profiled four of OWAA’s founders — Morris Ackerman, Cal Johnson, Jack Miner and Edward G. Taylor. This installment looks at the other four founders – Hazel Clements, Peter P. Carney, El Comancho, and Buell Patterson.

Hazel Clements (1891-1967)

Often part of OWAA conference agendas is a storytelling session during which attendees take to the microphone to relate personal outdoor experiences. In short order it has become a popular and well-attended event for entertainment, including some laughs.

Retha Charette told of her adventures hiking the Appalachian Trail. Steve Griffin talked about nearly tossing out a carefully prepared soup by accident. Christine Peterson gave an account of helping her husband and his brother track an elk they’d shot after discovering both men were color blind and unable to see the blood trail.

If such a storytelling event had been in place nearly 100 years ago when OWAA was being formed at an Izaak Walton League convention in Chicago, it’s a safe bet Hazel Clements would have shared some doozies.

Long considered a mystery in OWAA circles, her signature on the Bill of Organization is the only evidence of her participation in the organization’s founding, and only then as Mrs. Hall Kane Clements.

The story she likely would have told that 1927 spring evening in Chicago happened eight months earlier when a plane she was aboard in Canada crash landed into a lake from a height of 300 feet.

“How far, gentle reader, have YOU fallen?” she asked in an article she wrote on the accident for the Cleveland Plain-Dealer. “Have you ever stood and gazed thirty stories to the street below and wondered what would happen if you were to find yourself falling through the air at the speed of something like 150 miles an hour?

“There is, I have found, at least one thing about an airplane crash. It doesn’t take long.”

She watched it unfold from a seat next to the pilot, who lost control of the plane while trying to turn it around in high winds.

“I didn’t know much about flying then,” she wrote, “and if I had realized the awful helplessness of the pilot to swerve a falling plane, I might not have been quite so thrilled as the great, grey rocks of the small island leaped up at us.”

Everyone on board miraculously survived the harrowing experience but not without injuries. Clements, who was catapulted through the fuselage on impact, suffered three broken ribs and her scalp was ripped from the crown of her head to just above the neckline. Misfortune turned to good fortune when picnickers on shore revved up their motor boat and came to the rescue as Clements and the others clung to the plane.

“In the silence which hung over the mess of wreckage, human and mechanical, that was strewn over that section of the lake, we could hear the staccato put-put of the boat coming nearer and nearer,” she wrote.

They were rushed to a hospital, where Clements stood by “shaking with a nervous chill” while others were treated for their injuries. Seeing that Clements also was injured, a hospital worker picked her up and summoned help.

“I found myself, to my surprise, with the whole hospital staff gathered around the bed into which I had been bundled,” she wrote. “My teeth were chattering so that the staff couldn’t or wouldn’t understand my protests that I was perfectly all right.”

Clements got the impression the hospital staff thought she was going to die from shock.

“However, being an altogether unamiable person, I decided that wasn’t my day for dying, and after the scalp had a few tucks and neat seams taken in it … I wanted to get away from that place,” she wrote.

She succeeded three days later and in four months began a 40-day tour flying with the Royal Canadian Air Force.

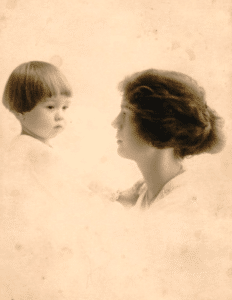

Photo Below: Hazel Clements with daughter Enid.

Flying became her passion with multiple trips into the Canadian bush that she called “gorgeous fun.” She helped do aerial mapping of timberland, flew fishery patrols over Hudson Bay and fire patrols over northern Manitoba, and had more than 50,000 miles of airtime doing roundtrip mail delivery in harsh winter conditions to the remote village of Seven Islands, almost 600 miles north of Montreal, Quebec.

“Somehow, in spite of a very whole-hearted enthusiasm for flying for several years, this flight to Seven Islands was my most vivid realization of what a miracle air travel can accomplish in overcoming the handicaps of distance, storms and inaccessibility,” she said. “We had come through a wilderness which for hundreds of miles at a time showed no sign of civilization or mark of any kind of travel.”

Clements also delivered written accounts of her aerial exploits to magazines and newspapers as “Letters of a Little Lady Vagabond.”

She was born Hazel Philomenia Kane in Olean, New York, and married shortly before her 17th birthday in 1908 to George H. Brenner, a tool shop worker. They had one daughter, Enid, in 1912 and divorced four years later. She remarried in 1921 to George Clements, who worked in newspaper advertising.

Clements also worked in advertising for the Cleveland Plain Dealer and Illinois State Journal before turning to writing. To make her stories more saleable in a male-dominated industry, she disguised that she was a woman by using a byline of Hal Kane Clements. Over time she adjusted it to Hall Kane Clements, perhaps to avoid confusion with Hal Clements, an actor and silent movie director of the same era.

In 1929, she launched a radio show – the Women’s Aviation Hour – on a New York station. Among her guests were pioneering female flyers Amelia Earhart, Phoebe Fairgrave Omlie, and Elinor Smith.

As hair-raising as her own flying adventures were, Clements found them less traumatic than standing before a studio microphone.

“I have never felt the least bit nervous flying over some of the most hazardous country I have ever seen, hundreds of miles from any civilization,” she said. “But when I get up before the mike, my knees wobble. My hands shake. Maybe I seem frightened! I’m going up one day soon and try broadcasting from a plane to see if I can only get over being afraid of the mike!”

Clements continued writing for newspapers in Chicago, Cleveland, and New York, but went a different direction once the United States got involved in World War II. She participated in the Victory Book Campaign, a program started by the American Library Association, American Red Cross, and United Service Organizations to collect and distribute books to members of the armed services.

In 1942, the USO hired her as associate director for its station in Port of Spain, Trinidad, where she worked 14- to 16-hour days. She was quoted in a short news item that circulated widely about a Maltese cat that adopted the USO station as its home and was fitted with proper identification. Clements said it was “the only cat in the army wearing ‘dog’ tags.”

Before retiring in 1963, she wrote a series of articles on Latin America for the U.S. Information Agency.

She died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1967, leaving a legacy of adventurous spirit.

Photo above: Peter P. Carney

Peter P. Carney (1882-1954)

None of OWAA’s founders had a more jumbled career than Peter P. Carney.

Messenger boy, grocery store clerk, amateur athlete, sports organizer and official, newspaper reporter, public relations director for firearms manufacturers and milk producers, and college lecturer. The last is the most peculiar. Carney was a grade-school dropout but developed enough life and business experience to land a job in 1949 teaching salesmanship at Boston University.

Born in England, he was the oldest of four children when his parents emigrated to America. After his father was killed in a mine explosion in Pennsylvania, his mother relocated the family to Trenton, New Jersey, where Carney quit school at age 9 to work for American District Telegraphy Company.

Looking for something better, he landed a job at age 12 as a grocery clerk making $3 a week while continuing to work for the telegraph company. He showed prowess in sports, winning more than 100 races in track and field as a short-distance runner. In 1906, he won the first of two New Jersey all-around track titles and became sports editor of the Trenton Sunday American, starting a string of jobs at several newspapers.

Carney dreamed of competing in the Olympics but was injured in 1907 and never competed again. The Netherlands reportedly tried to hire him as its Olympic coach in 1914, but it didn’t materialize.

He turned to bowling, where he was individual champion or runner-up of Trenton over a five-year period while captaining the five-time team champion.

To ensure ready-made fodder for his columns in the Trenton State Gazette, Carney created local baseball and basketball leagues.

In 1909, he took a newspaper job in Philadelphia and moonlighted as a referee in that city’s Interscholastic Basketball League. A year later he formed the Philadelphia Basketball Officials Association.

All the while he was still living in Trenton, where he became involved in that city’s chapter of the Amateur Athletic Union. He served five years organizing track meets before he was expelled in 1915 for publicly accusing the chapter president of orchestrating an illegal election of officers. Of the ouster, a Philadelphia Inquirer sportswriter opined: “It is evident that Mr. Carney refused to look upon the side of the bread with the butter and will now be left only the crumbs.”

The year wasn’t a total loss for Carney. He was elected vice president of the Philadelphia Sporting Writers Association, landed a job as editor of the National Sports Syndicate, and began doing public relations work for Winchester Repeating Arms.

He parlayed the Winchester job into interviews and information for his coverage of trap shooting over the next decade. His focus on trap shooting provided him a national audience. A Memphis newspaper declared “It is doubtful if any writer on subjects pertaining to guns and ammunition is better known than Carney.” His extensive coverage of shooting sports chronicled the participation of professional baseball players, royalty, and women.

Photo above: Peter P. Carney (1949)

He also wrote about hockey, ice skating, roller skating, and snow skiing.

Carney’s promotional savvy surfaced in 1921 when he arranged 6,000 tickets to be sold at Winchester stores for the Jack Dempsey title fight against Georges Carpentier. The bout drew 91,000 fans and generated the first million-dollar gate in boxing history.

Carney then landed a position as advertising director for Remington Arms, but that, too, was short lived when he began two PR jobs far removed from the work he had been doing – one with a dairy producer and the other with New York’s Grand Central Palace, the largest expo hall in the country.

The dairy business seemed to suit him. Until Liberty Dairy hired him, his only connection to dairy products was an appetite for milk. He reportedly drank two quarts a day. He launched a radio program on KDKA radio in Pittsburgh that focused on the nutritional value of milk, and later became president of the Greater Pittsburgh Milk Dealers’ Association.

The lecture position at Boston University put him on location for his last job as wholesale manager for Herlihy Brothers Dairy in nearby Somerville, Massachusetts.

El Comancho (1867-1940)

Photo above: “El Comanco” Photo retrieved from Historylink.org.

Walter Shelley Phillips was a man of many works … and many names, most given to him by American Plains people with whom he mingled for a good part of his early life.

The one that stuck was a spinoff of Comanch or Comanche, a nickname attributed to different individuals. Phillips tweaked it to El Comancho, and it became his byline on thousands of nature stories, 11 books, seven unpublished manuscripts, and hundreds of drawings and photographs, most of which are archived at the University of Washington.

Phillips was born in 1867 in Illinois, the son of a Civil War veteran who moved his family by covered wagon a year later to the Nebraska Territory, settling in Otoe tribal hunting territory where the town of Beatrice was soon established.

His father worked as a surveyor for the railroad, became postmaster and then mayor of Beatrice.

Phillips, an elementary school dropout, spent his childhood days playing with Otoe children and hunting and fishing with Otoe adults.

His first job was hanging telegraph lines, after which he hired on as a hunter providing fresh meat to a railroad crew plotting a route from Nebraska to Montana. Roaming the Black Hills, the Rockies, and land that became Glacier National Park put him among even more Native American tribes – Blackfoot, Crow, and Sioux among them. He learned their languages, stories, and how they lived, all grist for his writing career.

He sold his first story to Forest and Stream magazine in 1887. Intent on improving his writing, Phillips moved back to Beatrice and took work at the local newspaper under an exacting editor, Lehman C. Peters.

Returning to Beatrice also reunited Phillips with a childhood friend, Rena Egleston. They married and eloped to Seattle, where he walked into the Seattle Telegraph newsroom with a dime in his pocket and a desire to be a reporter. He was hired but lost the job when the Seattle Post-Intelligencer bought the Telegraph.

Phillips then landed a job as reporter and illustrator with Chicago-based Northwestern Lumberman, a trade magazine for the timber industry. During a seven-year stint with the magazine he polished his drawing skills at the Chicago Art Institute, a move that enabled him to illustrate his articles and books.

He bounced back and forth between Chicago and Seattle as his writing career blossomed into other magazines, including Field & Stream and Forest & Stream.

In 1904, Phillips created his own magazine – Pacific Sportsman – and ran it for several years before selling it to Outdoor Life. He wrote a column for that magazine over the next decade.

By 1920 he’d written and illustrated a half dozen books, cranked out a syndicated newspaper column titled Teepee Tales, and begun traveling from coast to coast giving lectures on his experiences. He claimed to have crossed America nearly 200 times on the lecture circuit, wearing out four automobiles in the process.

Izaak Walton League president Will Dilg recruited him to make presentations on stream conservation and establish new IWLA chapters in the process. Frequently dressed in a corduroy suit and donning a Stetson hat, Phillips gave nearly 500 lectures over a five-year period. He further extended his reach – and his reputation – by doing a regular program on WMAQ radio in Chicago.

He made up for a lack of formal education through reading and became well-versed in biology, geology, and natural history.

“Why I’m so well known,” he once said, “that I couldn’t steal a man’s horse, couldn’t burn a barn, couldn’t rob a bank, couldn’t steal another man’s wife, without someone seeing me that knew me.”

He settled in the Black Hills of South Dakota at Twelve Mile Ranch, where he spent his time painting, collecting fossils, prospecting for gold, and writing before making plans to move to California and live with a daughter.

He died in 1940 in Seattle, reportedly from cerebral hemorrhage.

Buell A. Patterson (1895-1958)

Photo above: Buell A. Patterson

A lot of people win awards. Few have an award named after them.

Buell A. Patterson is one of those few. Long associated with newspapers, radio, and public relations, Patterson was the first president of the Publicity Club of Chicago when it formed in 1941. The club annually recognizes the best use of technology with the Buell A. Patterson Award.

Although Patterson spent the latter part of his life in public relations for a variety of businesses, it’s not how his career began.

He attended the University of Chicago, where a 1914 Chicago Tribune article indicates he was a prospect for the school’s football team coached by the legendary Amos Alonzo Stagg. Two years later he was on the Maroons’ swim team that shared the championship of the Western Conference, now the Big Ten Conference.

After graduating, Patterson became a sports commentator and built a solid reputation broadcasting major college football games, including Notre Dame matchups against Navy and Southern Cal in 1928 – the season when Irish coach Knute Rockne gave his famous “win one for the Gipper” halftime speech. A year later Patterson joined WJR radio in Detroit and continued announcing football games. While working at WJJD in Chicago in the 1930s, he also did on-air book reviews and handicapping of horse races.

Patterson added newspaper writing to his résumé in the 1920s and continued for almost 20 years. Hearst Newspapers published his Rod and Gun stories, and he added two syndicated columns – America Out of Doors and Dog Chats – that reached 110 major daily newspapers.

“The backwoods are about tops for enlightening one on character,” Patterson wrote in one of his America Out of Doors columns. “If anyone wants to discover what manner of man any individual is, there is no more accurate measuring stick than a trip into the wilds.”

He had affection for dogs, writing in a 1940 column that “often I have wished for the time, the money, and the land to have a dog of every breed … Under ideal circumstances it might work out, but in truth it would be a difficult venture.”

Photo above: Buell Patterson at the University of Chicago.

Despite the column writing, Patterson never strayed far from a radio microphone while working in the publicity department of Chicago station KYW. In 1930, he announced speed boat races on the St. Joseph River in South Bend, Indiana, where loudspeakers carried his description of the events to 30,000 spectators.

Public relations appealed to Patterson, who founded his own firm in Chicago before taking advertising sales or PR jobs with Curtiss-Wright Corp., American Airlines, Pan-America Grace Airways, and U.S. News & World Report.

From 1939 to 1942 was a particularly transitional period for Patterson. American Airlines hired him in 1939 as central district public relations representative based in Chicago. Two years later he helped launch the Publicity Club of Chicago and was elected its first president. American promoted him in 1942 to publicity director working out of New York City.

While working in the airlines industry, Patterson continued his outdoor writing. He joined the North American Sportsman’s Bureau, a syndicate that distributed his columns to numerous newspapers along with the work of others affiliated with OWAA – J.N. “Ding” Darling, Cal Johnson, Robert Page Lincoln, Sigurd Olson, and others.

In 1948, Patterson left American Airlines to become director of the public relations division of the U.S. News & World Report but reversed course in 1951 when Pan-American Grace (Panagra) Airways hired him as its PR director. He sometimes wrote about fishing opportunities related to Panagra flight destinations.

He left Panagra in 1954 to become an account executive with Communications Counselors, Inc. In that capacity, he accompanied the Shenandoah Apple Blossom Festival queen and her mother on a promotional trip to Havana, Cuba.

On the return trip to New York, Patterson died of a reported heart attack during an overnight stopover in Miami.

Read more OWAA history:

Dinner in Chicago, 1927: The night outdoor writers founded OWAA

Writers who changed outdoor journalism: The founding of OWAA